By Bibiana Alcântara Garrido*

In its first edition of 2026, the newsletter Um Grau Meio interviews Arnaldo Carneiro, coordinator of the Amazon Regional Observatory of the ACTO (Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization).

The function of ACTO is to promote cooperation between the eight Pan-Amazon countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela), with a focus on protecting ecosystems through sustainable development.

Sign up to receive the newsletter for free in your e-mail every second Monday.

At ARO, Arnaldo Carneiro and his team are focusing on climate change, deforestation, biodiversity, fires and water, studying the future vulnerability of the Pan-Amazon to forest fires and the relationship between forests and the ocean.

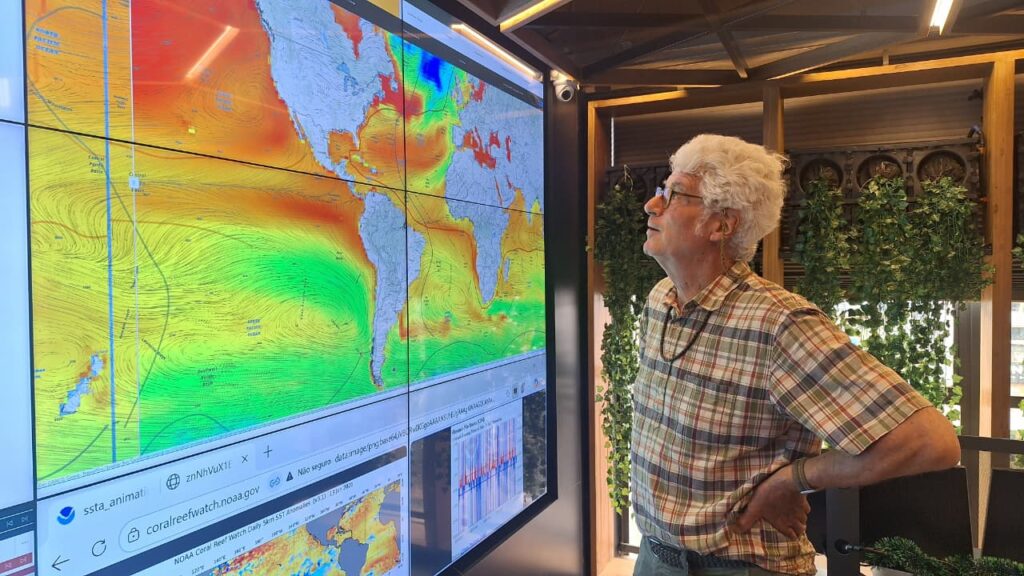

Researcher Arnaldo Carneiro at OTCA headquarters in Brasilia (Photo: Bibiana Garrido/IPAM)

Geographer, landscape ecologist and retired researcher from INPA (National Institute for Amazonian Research), he spoke to Um Grau e Meio about Amazonian integration, the gaps in tackling the climate emergency and the idea of creating a collective NDC for the region.

Read on.

What is the Pan-Amazon?

The Pan-Amazon is a concept that was constructed by Brazil. Brazil has always referred to the Amazon as a piece of its country, but when it realized that the Amazon has spaces outside of it, it called this the Pan-Amazon.

It’s an expression that integrates the Amazons of the other eight countries. But when you go to these countries, Pan-Amazonia is an expression they don’t use. They use “Amazon” to talk about the whole.

Nowadays I refer to the Brazilian Amazon, the Colombian Amazon… and when I’m meeting in the countries, we talk about the Amazon as a whole.

How has the Treaty signed in 1978 in Brasilia kept pace with the changes of the last 50 years?

If you look at the geopolitics of the time, you’ll find many dictatorships around the Amazon, including in Brazil. The military’s main concern was maintaining territorial sovereignty. So it was in this environment that the TCA (Amazon Cooperation Treaty) was created.

As history progressed, the issues evolved, ACTO adapted and these issues were incorporated. Created in 2021 by ACTO, the ARO (Amazon Regional Observatory) serves as a reference center for essential information on the shared and sustainable management of the Amazon.

At the moment, the big topic at the ARO is the issue of climate change and the dangerous trajectory we are on, including in the Amazon, which could lead us to a point of no return.

What have been the main advances in Amazon conservation over the period? And what gaps remain?

If we look at a graph, there was a moment of great expansion in the Amazon. In this eagerness to integrate so as not to surrender, the military began to promote the creation of infrastructures, let’s say, between the 1970s and 1990s. In the 1990s, the Real Plan created another peak in deforestation in the Amazon, because timber consumption also grew.

In the 2000s, Marina Silva brought civil society into the government and had a brilliant information transparency movement, creating an absurd capacity in science and NGOs in the Amazon. The government received a barrage of contributions, analyses and suggestions for public policies, which, when properly applied, had a huge impact on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. If you look at the curve, in the 2000s we really brought deforestation down to levels that are similar to today.

Many protected areas and indigenous territories were defined in the 2000s and 2010s. These were decades of great growth and solutions for quilombola and indigenous rights. We still have some outstanding issues, a huge socio-environmental debt. But we have come a long way.

We have also learned that a slice of deforestation (30 to 35%), which I treat as social, is carried out by small producers who are in settlements, riverside dwellers, all unassisted and with little access to solutions that could reduce their impacts.

The challenge is to implement a series of policies geared towards these social groups that allow them to integrate economically and socially. I think we’re still dragging our feet on this agenda.

How do regional and global geopolitics influence this scenario?

Today, we are already experiencing extreme events in the Amazon. The big question is who is the villain in this story. The question is still about the global role and the regional role.

The influx of moisture into the Amazon from the Atlantic depends on ocean temperature: if ocean temperature rises too much, we have drier weather events in the interior of the Amazon. If ocean temperature drops too much, the opposite happens, resulting in large flood cycles.

This gives us an idea of the global impact, because it’s pollution from North America that determines the temperature of the North Atlantic. It’s global warming caused mainly by Europe and the United States.

This is an issue that we bring up to the foreign ministers, because climate change in the Amazon has a global factor, which is the Northern Hemisphere. We’re from the southern hemisphere. So this brings a North-South political agenda into ACTO.

How is the region organized to deal with climate change?

We’re going to start running international campaigns. Our communication campaign has to go beyond this radius of eight ACTO countries and expand to Europe, the United States and Asia. We have to be in the media and forums on a permanent basis.

The world has gotten used to it and the media loves to publish deforestation data and the role it plays in climate change. So when the world sees this, it thinks that all the impact on the global climate comes from deforestation in the Amazon. And this is untrue. In a way, it’s consumption patterns in the northern hemisphere sustaining emissions that are creating impacts on the Amazon.

In 2024, for example, we had a major drought and major fires. This is something else that interests us a lot: the extent to which climate change creates vulnerabilities in the Amazon and predisposition to fires. This year we are starting a project with a tool to have a much more accurate look at fires, with a very rapid frequency.

When you look at our national plans and commitments, each country defines its NDC. But we are colonized countries, aren’t we? We tend to focus a lot on mitigation: “I need to show that I’m reducing deforestation, that I’m reducing fires, that I’m reducing my impact”. When you look at adaptation, I’d say we’re not putting too much stock in it.

There are a number of factors that we have to start thinking about for Amazonian populations, whether urban or rural, that we’re not thinking about today.

The last 11 years have been the hottest on record, with the worst temperatures in 2023, 2024 and 2025. What are the impacts of this reality on the Pan-Amazon?

I would say that adaptation is going to be a serious problem for Amazonians. The scarcity of rainfall or the extreme abundance of rainfall, which generates another impact, in addition to the heat. Cities in the Amazon already form heat islands, they are not well adapted to what lies ahead. Whether in small, medium or large cities, buildings are not adapted to climate change and high temperatures.

Does ACTO intend to create a “collective NDC” for the Amazon countries?

There was an attempt, a movement last year, but it didn’t prosper as we would have liked, precisely in order to have an Amazonian NDC.

If you look at the Brazilian NDC, it refers to programs that are associated with the Amazon, for example, the PPCDAm. Other countries don’t all do this. They often don’t make explicit reference to an intention regarding the Amazon.

What interests us is looking at the actions. We’re going to do some monitoring and some critical analysis, so perhaps we’ll have more influence when it comes to revising the agenda.

How can we reach a consensus on climate when Amazonian countries are following opposite paths? Brazil, for example, with new fossil fuel exploration fronts, and Colombia, which has declared its portion of the Amazon oil-free.

On this particular issue of oil, there was no consensus at ACTO. Some Amazonian countries are heavily dependent on oil and gas exports. So each country has to follow its own economic strategy.

In 2026, what would be the best news for the protection of the Pan-Amazon?

The best news for 2026 would not be a single announcement, but a clear realization that the Pan-Amazon region has entered a positive turning point and showing that regional cooperation, science and funding can work together.

Also, the Amazon should no longer be understood only as a “threatened forest”, but as a planetary infrastructure for the regulation of climate, water and biodiversity, necessary for food, energy and climate security in South America and the world.

*IPAM journalist, bibiana.garrido@ipam.org.br