By Bibiana Alcântara Garrido*

In a planet overheated by the burning of fossil fuels, alternatives to oil capital can benefit regional development without further increasing carbon emissions that aggravate climate change.

In this context, researchers propose a way out to guarantee sufficient resources to compensate states and municipalities for not exploiting oil in the Amazon: the Green Royalties Fund.

The creation of the Green Royalties Fund with 19.9 billion dollars would compensate states and municipalities directly affected by the non-exploitation of oil in the Equatorial Margin with an annual remuneration of 2.2 billion dollars for an indefinite period.

The calculation by IPAM (Amazon Environmental Research Institute) was published at the beginning of April in an article co-authored by the Museum of Tomorrow, PUC-Rio (Pontifical Catholic University) of Rio de Janeiro and UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) in the scientific journal Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation.

According to the researchers, the annual income from the proposed fund – based on the Selic rate at 11.25% – would be enough to pay states and municipalities the equivalent of what would be generated by oil exploration over a 27-year period.

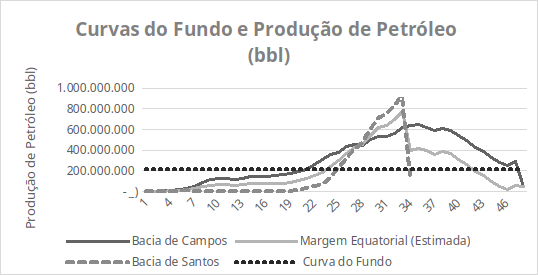

Unlike the profits obtained from the sale of barrels of oil, which tend to fall with the natural reduction in production after years of exploration, green royalties offer more stable compensation in the long term. See the graph:

Oil production curves, in barrels per year over time, and equivalent income curve of the Green Royalties Fund (Source: IPAM)

“The generation of oil royalties tends to suffer variations, either because of the form of exploitation itself or because of fluctuations in the price of the commodity. What’s worse, in today’s world, where the aim is to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, the tendency is for the price of oil and its derivatives to fall in the medium and long term, as alternatives become viable,” says André Guimarães, executive director of IPAM and lead author of the article.

“The green royalties proposal is in line with this reality, as it provides for the supply of resources to states and municipalities in a stable and permanent manner over time. In addition, there would be no risk of spills or accidents, which would often cause irreparable damage to these Amazonian regions,” he adds.

Overcoming the dichotomous debate

The study is being released in the midst of a debate about authorizing oil exploration on the Equatorial Margin, in the Amazon River Mouth Basin. In February, technicians from Ibama (the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources) recommended against drilling wells in the region off the coast of Amapá.

The pressure for exploration, reflected in public speeches by authorities such as President Lula himself (PT) and the Minister of Mines and Energy, Alexandre Silveira, contradicts the commitments made by Brazil to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 53% by 2030.

Guimarães points out that it is necessary to overcome the dichotomy between “authorizes” and “does not authorize” in order to deepen the debate.

“The discussion about oil in the Equatorial Margin is still very dichotomous: either ‘I’m for it’ or ‘I’m against it’. We need to overcome the dichotomy and deepen the debate. That’s why we want to add another element to the conversation, so that states and municipalities in the Amazon can benefit without oil exploration, without the associated risks and without the increase in carbon emissions inherent in this activity,” says the author.

From bills to financing

To calculate the Green Royalties Fund proposal, the authors consider the production of 10 billion barrels of oil in 27 years of exploration in the Equatorial Margin and the price of 67 dollars per barrel – the average of the projections from 2030 to 2050.

Thus, the profits from exploration would amount to 24.8 billion dollars a year. If a rate of 15% is applied to this amount, which is the proportion historically distributed as royalties in Brazil, there would be 3.7 billion dollars a year in royalties: 2.2 billion dollars for states and municipalities and 1.5 billion dollars for the federal government.

“The Green Royalty Fund established at 19.9 billion dollars considers that the federal government would give up its share of the royalties. This is to be expected if the Brazilian state believes that oil exploration goes against its own responsibilities towards the population in terms of climate, habitability and conditions for agricultural production. However, another option is considered in the article: if the federal government wants to receive its share of the royalties, then we’ll need a fund whose amount reaches 33.1 billion dollars,” explains Álvaro Batista, a researcher at IPAM and one of the authors of the study.

The researchers’ suggestion is that the National Treasury could contribute seed capital for the structuring of the Green Royalties Fund, inviting other countries, as well as private sources of capital, to join the Brazilian effort.

Oil profits don’t result in social gains

The article also presents an analysis of the results of receiving oil royalties in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The state is home to 80% of all the country’s offshore reserves, which makes its municipalities dependent on the activity.

However, oil profits have not translated into social gains: between 2014 and 2023, ten Rio de Janeiro cities concentrated 63% of the 10 billion dollars in oil royalties received by the state. Only two of them registered any improvement in the HDI (Human Development Index): Maricá and Campos dos Goytacazes.

“The data exposes a disconnect between millionaire transfers and effective improvements in quality of life, with the occasional exceptions of Maricá and Campos, which showed a slight improvement. The case highlights the challenges in managing oil resources to promote sustainable development,” says Anna Aguiar, a researcher at PUC-Rio and one of the authors of the article.

“The Museum of Tomorrow’s scientific research team works on future scenarios that are not a mere repetition of the present. Hence our joy at collaborating with IPAM, UFRJ and PUC-Rio on this study”, comments Fabio Scarano, one of the authors, a full professor of Ecology at UFRJ and curator of the Museum of Tomorrow, in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Energy transition

The Brazilian presidency of COP30 puts climate finance, a just energy transition and mitigation and adaptation agendas among its priorities. In a letter published at the beginning of March, Ambassador André Corrêa do Lago defends COP30 as the milestone for a “post-negotiation” phase within the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change).

For the authors of the study and the proposal for the Green Royalties Fund, increasing ambition and even implementing the climate targets already assumed by Brazil necessarily imply leaving the oil underground.

“The signal that Brazil could send out to the world is: ‘we’re going to stop exploring for oil because we understand that it’s bad for the health of the planet, and therefore for our health. But we’re not going to harm the states and municipalities. We’re going to benefit them with another form of financing, which would be green royalties, avoiding the climate damage that would certainly be caused by fossil carbon emissions into the atmosphere’. With this, the resource could be invested in more conservation, restoration, in the energy transition, as well as in sustainable activities, with gains for the planet’s climate,” adds Guimarães.

*IPAM communications specialist, bibiana.garrido@ipam.org.br

Photo: The mouth of the Amazon River, on the Equatorial Margin (Photo: Carlos Durigan)