By Bibiana Alcântara Garrido*

The Cerrado has lost natural water in 91% of its watersheds over the last four decades. The figure takes into account the mapped water surface area, measured in hectares. Last year, the surface area of natural water in the basins comprising the biome was 28.8% below the historical average (1985-2024), occupying around 1.85 million hectares.

Even against this backdrop, the increase in anthropogenic water surface – due to human influence, such as in reservoirs – guaranteed the biome a “false positive” to close 2024 with an 11% increase in total water surface compared to the average.

The data from the annual and monthly mapping of the water surface between 1985 and 2024 are from the MapBiomas Água initiative, integrated by IPAM (Amazon Environmental Research Institute) and were released this Friday, March 21, in anticipation of World Water Day, celebrated on March 22.

Connected risks and insecurity for 68 million people

The drop affects irrigation in agricultural areas of the Cerrado, which accounts for 60% of national production and half of the country’s irrigated agriculture; as well as the flow to other biomes, such as the Pantanal, which has suffered the most from droughts throughout the historical series.

Considering the supply for human consumption, at least 68 million people are at risk of water insecurity throughout the area of the basins, according to IPAM’s analysis, due to the loss of natural water in the Cerrado.

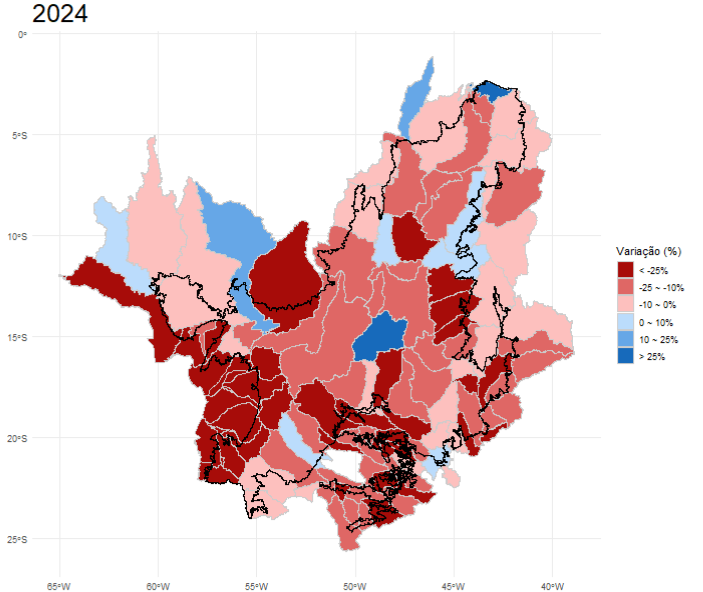

Where the loss was greatest

“The five river basins that have lost the most natural water surface are in the region of the Upper Paraguay River plateau, at the connection between the Cerrado and the Pantanal. This region is home to the headwaters of the main rivers that regulate flood pulses in the Pantanal and the decrease in natural water surface is critical for the functioning of both biomes,” says Dhemerson Conciani, a researcher at IPAM and the MapBiomas network.

The Nabileque River basin has seen the greatest percentage loss compared to the historical average. Located where it meets the Pantanal plain, it lost 90% (-73,200 hectares) of its natural water surface between 1985 and 2024.

Next in line are: the Rio Negro basin in Mato Grosso do Sul (88% reduction, -70,400 hectares); the Rio Paraguay basin (71% reduction, -235,000 ha); the Rio Miranda basin (70% reduction, -11,000 ha); and the Rio Madeira basin (65% reduction, -50,000 ha), the latter on the border with the Amazon biome.

Below, these basins are represented in the outline of the left bank, in dark red.

Change in natural water surface in Cerrado river basins between 1985-2024 (Source: MapBiomas Água)

In addition to the Cerrado-Pantanal transition, losses were also concentrated in the agricultural frontier of Matopiba (which includes municipalities in Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia); and on the border between São Paulo and Minas Gerais.

In Matopiba, the most affected basins were the Grande São Francisco 1 (-60%, -1,431 ha) and Carinhanha (-58%, -900 ha), while the Araguari river basin (-45%, -1,861 ha) led the loss of natural surface in the southern portion of the Cerrado.

Where the water goes

If the Cerrado’s natural water is disappearing, artificially stored water continues to increase. In 2024, 68.5% of the basins encompassed by the biome gained water surface due to anthropogenic influence.

“The construction of hydroelectric dams and large reservoirs in the biome has contributed to this increase, such as the Serra da Mesa hydroelectric reservoir on the Tocantins River in Goiás. Although their level is controlled, these reservoirs are supplied by natural water bodies that are directly affected by changes in land use and deforestation, as well as climate change,” says Julia Shimbo, a researcher at IPAM and scientific coordinator of the MapBiomas network.

The 11% gain in the biome’s total water surface compared to the historical average was driven mainly by the increase in reservoirs (+54%) and hydroelectric plants (+93%).

Deforestation affects water security

One of the factors influencing the drop in natural water surface is deforestation.

The clearing of native vegetation, especially in areas close to rivers, streams and springs, alters the protection of aquatic ecosystems and the ability of biomes to self-regulate floods and droughts, which depend on this dynamic to maintain irrigation flows and natural hydrological cycles. The consequences are immediate and medium to long-term negative impacts, the researchers warn.

According to an IPAM analysis using data from the Cerrado Deforestation Alert System (SAD Cerrado), around 31% of the watersheds with natural water loss in the Cerrado saw an increase in deforestation between 2023 and 2024.

Deforestation also alters the quantity and quality of water for human use, affecting water security, energy generation, agriculture and public supply.

“The removal of vegetation causes a decrease in groundwater recharge and river flow, thus reducing water availability. In addition, deforestation increases land erosion and sedimentation in channels, directly impacting water quality. This scenario worsens water, energy and food security, which depend on the availability and quality of water for their activities,” explains Fernanda Ribeiro, a researcher at IPAM and coordinator of SAD Cerrado.

Ribeiro adds: “The control of deforestation in the Cerrado, the effective implementation of the Forest Code and the protection of sensitive areas, such as Permanent Protection Areas that shelter springs, are measures to remedy the loss of natural water in the biome.”

*IPAM journalist, bibiana.garrido@ipam.org.br

Cover photo: Perdizes River waterfall, in Baliza (GO) (ISPN Collection/André Dib)