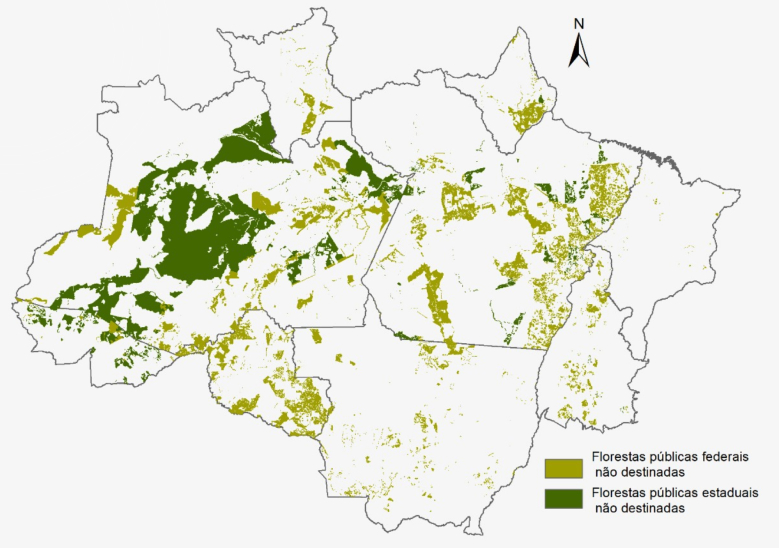

In the Amazon, about 51 million hectares of forests, an area equivalent to twice the state of Rio Grande do Sul or the size of Spain, is one of the most precious assets of Brazilians. These are the so-called non-destined public forests.

Non-designated public forests must be geared towards conservation or the sustainable use of their resources, especially by indigenous and traditional populations. Unfortunately, these forests have been the target of land grabbers and illegal deforestation, usurpers of the public good who take land that belongs to the collective.

Scattered in different parts of the Amazon, these dense forests play a fundamental role in the climate and water balance at local, regional and global scales: much of the distribution and maintenance of rainfall in the country depends on the ecological integrity of these green massifs.

However, by the end of 2020, more than 14 million hectares of these forests, or 29% of the total area, were illegally registered as private property in the National Rural Environmental Registry System (CAR). As the CAR is self-declaratory, land grabbers draw on the system supposed rural properties in non-allocated public forests, to simulate a right over land they do not have.

Non-designated public forests must be geared towards conservation or the sustainable use of their resources, especially by indigenous and traditional populations. Unfortunately, these forests have been the target of land grabbers and illegal deforestation, usurpers of the public good who take land that belongs to the collective.

Scattered in different parts of the Amazon, these dense forests play a fundamental role in the climate and water balance at local, regional and global scales: much of the distribution and maintenance of rainfall in the country depends on the ecological integrity of these green massifs.

However, by the end of 2020, more than 14 million hectares of these forests, or 29% of the total area, were illegally registered as private property in the National Rural Environmental Registry System (CAR). As the CAR is self-declaratory, land grabbers draw on the system supposed rural properties in non-allocated public forests, to simulate a right over land they do not have.

Deforestation in non-designated public forests generated the emission of around 1.49 billion tons of CO2 equivalent to date. If this invaded area were consolidated as a rural property, the felling associated only with compliance with the Forest Code could release another 1.43 billion tons of CO2 equivalent into the atmosphere in about a decade, which puts Brazil even further away from its goals , agreed under the Paris Agreement, for the mitigation of climate change.

The advance of land grabbing in these forests would also place the entire Amazonian system at the so-called “point of no return”: once exceeded, the Amazonian environment would irreversibly lose its ecological functions, which would lead to an increase in temperature on a regional and global scale and, consequently, a cascade effect, with changes in rainfall, water supply, food production, hydropower generation and, finally, in the country’s economy and the well-being of all Brazilians.

The main stimulus for land grabbing in public forests in the Amazon has been real estate speculation. The grileiro “invests” in the illegal occupation of the land and profits in three ways: first, with occupation free of charge, often using “oranges”; second, with the illegal sale of timber of commercial value; later, with agricultural production, largely as a facade, or with the sale of that land to another occupant, who bears the environmental liabilities.

Given this scenario of destruction and usurpation of public property, it is urgently necessary to initiate a coordinated, consultative and participatory process, based on science, to assess the main priorities for the allocation of these public forests not designated by the state and federal spheres. Only the allocation of these areas, as required by the Public Forest Management Law of 2006, can show land grabbers that they are not “nobody’s land”. It is critical, therefore, to interrupt the land regularization of illegal areas, an act that only encourages more illegal occupation.